Friday, April 27, 2012

Why Don't People Read More?

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

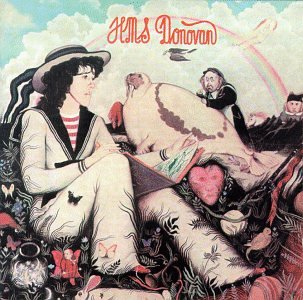

H.M.S. Donovan

Most people only knew the Donovan who sang “Mellow Yellow,” a delightful song, but hardly the full range of Donovan's repertoire. And very few people may recall his cameo appearance in the movie, If It's Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium, in which he sings “Lord Of The Reedy River.” That this incredibly romantic song is included on HMS Donovan is a testament to the emotional range represented by the album. It was produced as a present to his young daughter. But, though it contains children's songs and poems, there is nothing tame about them. You have only to listen closely to the song of “The Walrus and the Carpenter” (from Alice In Wonderland) to know that.

Another interesting thing about the album is the artist who did the cover and the interior art (in the earlier printing, a bonus poster was included) – a fellow who simply called himself Patrick. Patrick also did the art that was supposed to appear on the Beatles album that eventually became the White album. Needless to say, this did not happen, and the art was eventually used for The Beatles Ballads and the EMI Dutch release of a love songs album, De Mooiste Songs.

My brother, David, researched Patrick some more and discovered that he is the Scottish artist and playwright, John Patrick Byrne. He is well known in Scotland and has published a children's book, Donald And Benoit. Mr. Byrne doesn't seem to play up his connection with the Beatles, so a fan set up a website for him. To quote from the bottom of the home page: "This is a website dedicated to the paintings of the Scottish artist John Byrne, the true renaissance man from Paisley. I thought about calling it 'ohforgodssakewhycan'tIfindJohnByrnes paintingsonthenet.com,' but, sadly, the domain name was already taken."

One last bit of trivia about Mr. Byrne -- his significant other is Tilda Swinton.

As for the other album whose cover Mr. Byrne painted, YouTube lists many of the songs on HMS Donovan. Unfortunately, the one for “The Walrus and the Carpenter” seems to have been recorded with a hand-held microphone off of someone's turntable, using a scratched LP. This version of “Jabberwocky” is much better.

And one of my all-time favorites, “Henry Martin,” is also well represented.

There are 28 songs on the album, and most of them can be sampled on YouTube. Once you've heard them, you may decide to download the songs from itunes. If so, it's an investment you won't regret.

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

The Heard Museum Book Store

In Phoenix, At Central Avenue and Encanto, you'll find one of the last surviving bookstores, The Heard Museum Bookstore. We specialize in books by and about Native Americans, and about Arizona travel, geology, and history. We have also have children's books and cookbooks. People often ask me which books are my favorites, so here are my (current) top ten.

EM'S FAVES (In No Particular Order):

Grand Canyon: Vault Of Heaven, by the Grand Canyon Association

Magnificent photographs and a very informative text, at a bargain price!

Grand Canyon's Long-Eared Taxi, by Karen L. Taylor

Find out why mules are the only animals that can ferry people into the Great Unknown.

Roadside Geology Of Arizona, by Halka Chronic

Learn more about the Geology Capital of the World – from your car!

Gem Trails Of Arizona, by James R. Mitchell

Catch gem fever and go looking for not-so-buried treasure.

Talking Mysteries, by Tony Hillerman and Ernie Bulow

Read what Hillerman and Bulow have to say about their lives and about writing.

The Arizona Cookbook, by Al Fischer & Mildred Fischer

Authentic Indian, Western, and campfire recipes

Forest Cats, by Jerry Kobalenko (photographs by Thomas Kitchin & Victoria Hurst)

An informative text with breath-taking photographs

Frequently Asked Questions About The Saguaro, by Janice Emily Bowers

Find out why the saguaro is truly the movie star of the desert.

Sheep In A Jeep, by Nancy Shaw & Margot Apple

A wild and wooly expedition!

Brighty Of The Grand Canyon, by Marguerite Henry

The adventures of a beloved burro, with delightful illustrations

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Belly-Button Rocks, Volcanic Tortoises, And Blue-Eyed Baboons

My husband and I just hiked one of our favorite trails: Peralta Canyon Trail in the Superstition Mountains. Each time we do this, the trail presents challenges, but also allows us to visit some old “friends.”

Take the Volcanic Tortoise. About the size of a Volkswagen Minibus, he is frozen in the act of climbing one side of the canyon. He may be the product of Caldera-type volcanic explosions that occurred between 8 and 15 million years ago, producing hundreds of feet of volcanic tuff (fused volcanic ash and breccia). If you've ever been to Frijoles Canyon to visit Bandelier National Monument, you've seen similar deposits. The holes in the deposits are from gas bubbles that were present as the ash fused and cooled. At Bandolier, the ash is Rhyolitic (it has a higher ratio of silica-to-Fe & Mg and tends to be colored tan to pink); in the Superstitions, the tuff mostly runs from Rhyolitic to Intermediate – though you can also find basalt there, suggesting that some of the magma in the original or subsequent volcanic activity was mantle rock.

The tortoise looks almost black, though that may be from desert varnish. His jaws are open – maybe he was reaching for some yummy vegetation when he froze. He's at the lower end of the canyon, surrounded by thick desert scrub and saguaros. The vegetation and rock debris make it very difficult to venture from the trail (though some intrepid teenagers climb the hoodoos alongside it from time to time). That tortoise could munch down all day and still not make much of a dent in the brittlebush, creosote, and jojoba bushes.

Ernie and I find it challenging enough just to hike to the end of the trail and back. Ernie could go much faster if I weren't holding him back with my camera and my less-than-buff muscles. But what I lack in speed, I make up for in stamina – I can hike for about 7 hours, if I must, and if I get regular breaks. That's what I keep telling myself as every single person on the trail, young to old, passes me by. Alas. Good thing I'm not competitive, or I'd probably hurt myself trying to keep up with them. The situation also has its benefits; my SF-writer's brain thinks up gizmos that could help hikers with physical challenges (most of us, I suspect). Maybe a sort of body framework for hikers, with boots, knee-pads, elbow pads, and gloves? Something that would absorb the shock of each footfall, and maybe give us a boost as we're climbing? Imagine how far we could go, what we might see! Heck, some folks might even want to wear them when they're doing housework. Fashion could change drastically – we'd all end up looking like robots.

I long for this gizmo as I labor up steps that make my knees creak. People in their 60s and 70s smile at me as I step aside to let them pass. They've got hiking poles – I'm hoping that's why they're faster than me. And in the meantime, Ernie the Mountain Goat is forced to stop regularly, to wait for me to catch up. I also stop to take some photos, but I wish there was some way I could convey the wonderful smells of the desert in the spring. Some of the plants are fragrant even though they aren't currently blooming. A cool breeze blows, helping to alleviate the hot sun. And I can't help but ponder the hoodoos.

The most famous hoodoos in the Southwest are in Bryce Canyon, in Utah. They're composed of a mixture of silt, sand, mud, clay, and limestone that has seeped into the lower layers from above. The limestone caps on the formations keep the columns from immediately melting away from the top down – the sides erode first. Figures seem to be emerging from the monocline and marching into the valley. As moisture erodes them, they end up with a coating that looks almost like stucco.

But the hoodoos in the Superstitions are different creatures. They're composed of that volcanic tuff, so their sides are harder and straighter. Sometimes they almost look as if they were carved with a knife. Yet, they still have that characteristic hoodoo look, as if they were rock creatures who are engaged in an incredibly slow march.

They line the top of the canyon on either side of the trail. Periodically, I stop to look at them, even talk to them (in polite tones). But I'm really looking forward to seeing one creature in particular, a goddess I call Belly Button Rock. I must thank her for letting me visit her enchanted valley, and hope for her blessing. I point her out to other hikers on the trail, who exclaim with wonder – they had never noticed her before, despite her profound presence (not to mention her fabulous midriff). Perhaps, in the future, they'll point her out to other hikers.

I stop to photograph some rocks that look like basin-and-range faulting in miniature. And I can't resist trying to capture a window of bright light shining through a formation. The last time I was here, I took hundreds of photographs – I was a budding geologist full of wonder. I still feel that way this time, but I don't need to snap as many pictures. Just as well, since we took 7 hours to complete the trail on the last visit, and it should only take 4 to 5.

Labor up the switchbacks at the West end of the canyon, and eventually you'll wind your way around to the point where you can see the Blue-Eyed Baboon, a cheerful sentinel whose head pokes above the Northern side of the trail. Blue sky peers through a hole in the formation. Yes, the hills have eyes, and they are blue.

The end of the trail is Weaver's Needle, and you get to walk among some of the hoodoos. If you were intrepid, you could keep hiking until you reached the petroglyphs of the Hieroglyphic Trail. But that's a long time between restroom breaks, so Ernie and I turn around and face the challenges of the downhill walk, actually more painful than the uphill climb. That's when the knees, hips, and feet really begin to complain as your full weight comes down on them, step after step. I'm REALLY longing for that sci-fi hiking-framework gizmo now. But still happy with beautiful Peralta Canyon Trail.

Still ready to go back again, every chance I get.

Monday, February 27, 2012

Powerhouse Knocks Your Socks Off

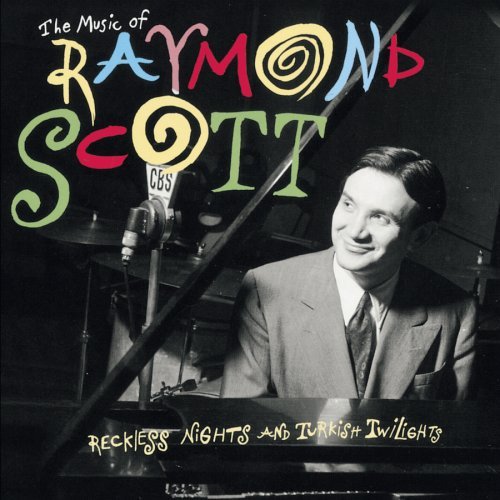

Recently we celebrated the 50th Anniversary of John Glenn's flight into orbit around the Earth, a feat that still fills me with pride. Though I also celebrate the fact that Yuri Gagarin and Valentina Tereshkova were the first man and woman in space, that flight was one of the great American achievements of the 20th century. But another great achievement celebrated its 75th Anniversary on that same date: the debut of Raymond Scott's best known composition, “Powerhouse.”

If you've ever seen an automated assembly line in action, you can't help but imagine “Powerhouse” playing in the background – it is truly the music of the Jazz/Machine Age. In a way, that technology is as Victorian as anything you'd find in a Steampunk novel, with its gears and perfectly calibrated interlocking parts. I can remember one Warner Brothers cartoon where a couple of ultra-polite chipmunks accidentally get transported to a canning plant inside a load of vegetables. Carl Stalling's arrangement of “Powerhouse” plays while these little guys try to avoid the machinery that processes and cans the veggies. When you listen to that rendition, you don't just hear the machines working – time itself seems to be marching off to some dazzling, relentless future.

Stalling's renditions of Raymond Scott's work are beefier than Scott's, since they're arranged for full orchestra. And the Warner Brothers orchestra recorded on one of the best sound stages in Hollywood. I grew up watching those cartoons (on the Wallace & Ladmo Show), and I ended up getting thoroughly spoiled by the high-quality animation and scoring. The wretched, canned music that accompanied cartoons in later eras is like fingernails on a blackboard to my ears. Fortunately, I can still get CDs with the good stuff on them.

My favorite Raymond Scott album is Reckless Nights And Turkish Twilights. If you look on Amazon, you'll notice that most of the reviews for it are 5 stars. It's a perfect collection. Some would say the sound quality isn't up to par with the great recordings of the 20th century, and that's true. But this album made me realize something about the music of Raymond Scott – it was actually written with that poor sound reproduction in mind. When this music is recorded in high fidelity, it's almost too much (though Carl Stalling certainly did a magnificent job with his arrangements.) I think the lower fidelity of this recording protects the listener from the full "manic" impact, giving you a chance to enjoy the performances and the composition.

And if you'd like the Warner Brothers/Stalling take on the subject, try The Carl Stalling Project. It will make you long for the days of those old big-band orchestras. If only there were nightclubs that still offered dinner, a big orchestra, dance performances by the likes of Fred & Ginger . . .

So I salute John Glenn on the anniversary of his flight into orbit. And I salute Raymond Scott for sending me into orbit. Here's to you, fellas.

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

The "Baby State" Turns 1.7 Billion

The state of Arizona is now officially 100 years old, semi-officially 1.7 billion years old (recent findings at the bottom of the Grand Canyon suggest that at least a few chunks of it are far older). There are many places in Arizona where that birthday can be happily celebrated, and one of them is the book store where I work.

The Heard Museum Book Store is located in the courtyard of the museum, right next to the Coffee Cantina, at Encanto and Central Avenue. It is one of the last surviving book stores in Central Phoenix. We specialize in books about the Southwest, Native Americans, and Arizona travel and history. Our courtyard is full of tables that sit under Ironwood trees, right next to a splashing fountain, where people who have just purchased books can sit, sip coffee, and enjoy the serenity. And you don't have to pay the entrance fee to shop there. It's the perfect place to explore the subject of Arizona's Centennial. In honor of that birthday, several books have been published about our history, and we carry them all.

My favorite is Jim Turner's Arizona: A Celebration of the Grand Canyon State. Whether you're an Arizona resident, a sometime visitor, or a fan of ARIZONA HIGHWAYS magazine, this is a book you must have in your collection. Though a lot of people in the world know a little bit about Arizona, Jim Turner knows a lot more, and what he knows is fascinating. He's put a wealth of interesting details into one handy book.

Arizona is the last of the territories in the contiguous United States to become a state. Our history is as unique as our geology – a point not lost on Turner, because he begins the first chapter with, “Eons ago, huge chunks of the Earth's crust called tectonic plates rammed into each other . . .” Beginning a book about Arizona's history with the tale of its geology is not a whimsical choice. We are what we are because of those tectonic plates – because of our latitude, our basin-and-range mountains, our volcanic history, and the inland seas that laid down the sedimentary rock that was eventually carved into the Grand Canyon by the Colorado River. That landscape of canyons, plateaus, mountains, valleys, and deserts is the setting for our “Wild West” history, peopled by Native Americans, cowboys, miners, adventurers, farmers, ranchers, soldiers, yahoos, scoundrels, scientists, and dreamers. Turner has stories to relate about all of them.

But don't get the idea this is a thick, dry tome of facts. The book is lavishly illustrated with photographs, maps, and illustrations. It is divided into chapters about each successive wave of populations, from the ancient ancestors of Native Americans to the post-war immigrants who drove here on route 66. The sections are accessible, more like magazine articles. You can peruse the text any way you like, from start to finish, or just by looking up the tidbits that interest you. Some may prefer to keep it on their coffee table, others will shelve it with their history or travel books.

I keep it where I can reach it easily. Like Arizona, this book is a treasure.

Thursday, January 26, 2012

Heaven, Hell, And Other Devices

I've published a new ebook, titled Pale Lady, (cover art by Ernest Hogan) and this is the freebee coupon code for Smashwords: EG36Y. Just apply it when you're checking out, and it will reduce the price to $0.00.

Now that I've made the pitch, I have to make a confession. I can be very naïve when I decide what books and stories to write. Or maybe I should say I'm oblivious. I never consider how people may react, except to hope that they'll enjoy reading my work. In the case of Pale Lady, the novelette I just published on Smashwords and Amazon as an ebook, I didn't worry that people may assume the story is overtly religious until I was getting ready to publish it. Pretty funny when you consider that it's a story about a bunch of dead people whose souls have gone to Purgatory. Yep – I'm a pretty big dope.

I'm also an Agnostic. I have spiritual inclinations, but I don't want to belong to a church or a particular religion. I don't disagree with religious folk, and I don't disagree with atheists, either. I think they all make good points, but I'm happy to discover the mystery of the cosmos as I encounter it. Yet as a writer, I have to admit that Heaven and Hell make wonderful literary devices.

Especially Hell. I have a feeling that the less you say about Heaven, the more accurate you're going to be. And God seems too complex a being to really capture as a character. The Devil, on the other hand, is a fairly down-to-earth kinda guy. And the ruined grandeur of Hell is irresistible. Dante's Inferno is much more readable than Purgatorio and Paradiso. Or at least, I think it is, because I only made it halfway through Purgatorio and couldn't finish it. The same is true of Milton's Paradise Lost. His description of Pandaemonium kicks butt, and I was fascinated when Adam asked an Archangel why the universe is so big if Mankind is the only intelligent race in it, and the angel told him that he just doesn't need to know the answer to that (apparently the mysteries of the cosmos are revealed on a Need To Know basis). I suppose I should read Paradise Regained some day, but should and will are two very different things. Besides, sequels hardly ever live up to the original.

I don't write about the Devil in Pale Lady. But I think he's a great character. Subtle he must needs be, who could seduce angels, writes Milton, in Paradise Lost.

On the one hand, it's interesting to ponder the fallen Angel, Lucifer, a grand and beautiful super-being who felt confident enough to challenge the Almighty for supremacy (although I often wonder if he was just trying to show God that He was wrong rather than take over). High Fantasy writers use this sort of Devil to represent absolute evil, characters like Sauron from The Lord Of The Rings. Even in The Hobbit, the dragon Smaug has some of the Devil in his personality – Tolkien warns that talking to a dragon too long can get you into trouble.

I think it's the Devil's human qualities that end up intriguing us the most. He took that fall because of his hubris, and that's a flaw we all share to one degree or another. The characters in Pale Lady also get into trouble because of their flaws. But you can say that about any book.

So it's probably my setting that could cause the most misunderstanding. The concept of Purgatory is that you're seeking redemption – you blew it, but maybe you can fix it. Some might see that as an attempt to proselytise. But religious instruction is not my bag – if I'm going to preach, it's more likely to be about conservation. I wrote about these characters in Purgatory for only one reason: I dreamed they were there.

Dreams aren't the inspiration for every single novel or story I write, but most of the time they're at least a factor. In the case of the dream that inspired Pale Lady, I wasn't remotely aware that I was dreaming – the place I found myself and the problems I had were quite daunting. Once I woke up, I knew I had to write the story.

I find the concept of being perched between two extremes irresistible, maybe because I think it's the human condition. We're edging toward Heaven or Hell in our lives – not so much spiritually, but in terms of how we're managing things, how happy we make ourselves and others, what we do in the world and what we suffer. I often feel compelled to write about characters who are trying to escape difficult situations and find some measure of freedom and self empowerment. My personal experience is that escape from metaphorical Hell or Purgatory takes a certain measure of self sacrifice and courage. I suspect that if those metaphysical places actually exist, that rule could only be magnified.

So that's my shtick. I'm not pushing Jesus, Mohammed, Buddha, or any other prophet, and I'm not one myself. I'm just a writer who has odd dreams. I hope you'll find them entertaining.

One last thing – it was my intention to publish Pale Lady as a free ebook and to use it to promote my other books. But because of the way I published the Amazon version, I'm not allowed to offer it for free on Amazon. Since I have a contract with them not to offer the book at a lower price on any other site, I have to charge $.99 as the list price. That's why I'm publishing this freebee coupon. Please use it and pass it on to anyone else who may be interested. You'll only be helping me if you do so.

Plus you're more likely to go to Heaven. (Kidding.)

Monday, January 9, 2012

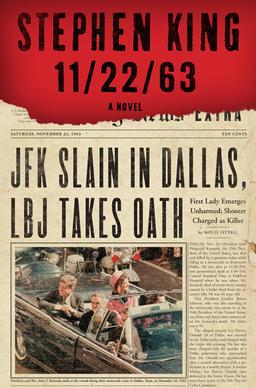

Time Is The Fire: 11/22/63, by Stephen King

I don't usually write reviews for the books of super-popular writers. They don't need my help to get exposure, and my voice would probably get lost in the crowd. But this time around, I really feel compelled to write about Stephen King's new book, 11/22/63, not just because I liked the book so much, but also because I was so fascinated by the ideas in the book.

Like King, I lived through the early sixties. I was born in 1959, so I was only four years old when JFK was assassinated. But that event was so shattering, so enormous to ordinary American citizens, for most of my childhood it almost seemed like it had just happened. It seemed that way right into the mid seventies. Also, I lived in Phoenix, Arizona, and though it's the biggest city in Arizona, in the sixties it was a big farming community, with cotton fields stretching as far as the eye could see. Culturally speaking, we were at least a decade behind the America you could see on your TV screen. So JFK still loomed big in our world. Yet the first thing that I read in 11/22/63 that really made me think that time travel might be a wonderful thing to do was not the idea that maybe someone could go back and prevent the assassination of JFK. It was the root beer.

I could taste that root beer he described in the book. And in Arizona, that experience had an extra dimension: the root beer was ice cold. If it's 107 degrees outside, and the humidity is less than 5%, drinking an ice cold root beer is a heavenly experience. When I was a kid, I was usually on foot when I went after the root beer, and sometimes I was even foolish enough to go barefoot, though the pavement could be incredibly hot. So the root beer hunt was a perilous adventure, one that offered truly fabulous rewards.

Nostalgia clouds our memories of the past. In most books about time travel, that isn't much of an issue – people go way back in time. So in this case, it's interesting that the character is only going back about 50 years. It's even more interesting that he isn't from that decade himself, he won't be born until the mid-seventies. Nostalgia isn't driving him at all, though he certainly develops a healthy dose of it once he's able to experience that root beer, as well as other delightful artifacts. Many other artifacts he encounters are not so delightful: racism, sexism, small town bigotry, and a resistance to putting really good books like Catcher In The Rye in school libraries, where they would actually do the most good. A man without a mission might just visit the past occasionally, stick to the root beer and the inexpensive golden-age comic books, avoid the jerks as much as possible.

But Jake (masquerading as “George”) does have a mission. In fact, he has more than one, and the JFK assassination isn't even the most important one. He has another rescue driving him, one that's a lot more personal, a friend whose life was changed by one terrible night when his father murdered the entire family. The friend was the sole survivor of that massacre, and was badly injured. Jake thinks first of him, and that's a good thing. If saving JFK was the only thing on his mind, that would be some serious hubris. Thinking you can stop the massacre of a family is also hubris, but most of us would try to do the same thing if we could. And like Jake, we would find out just how dangerous and daunting that is. First of all, guys who are capable of murdering their entire families possess a terrible vitality, and above-average cunning. Most people have no idea how to fight a dragon like that. So this is one of the many challenges facing Jake.

Another challenge is that time itself seems to resist his efforts. The deck is stacked against him. Can he defeat this law of nature? Yes and no, and that's the key to this book. I don't want to spoil it for you by describing what happens, you need to sit at the edge of that seat yourself. But this story really inspired me to reconsider the concept of time travel. Most scientists will tell you it's not possible. But people also said that about traveling faster than Mach 1, and we're way past that now. If you consider that anything is possible, then you have to consider that time travel is one of those possible things. And if it's possible, what are the consequences?

When someone tampers with history, does the timeline lurch into a new path? Or is damage done on some level we can't perceive until the dissonance is so severe, the weave of time/space starts to come unraveled in some places? Will time act to protect itself? King may not be the first to ponder those questions, but his approach is not the usual one taken by writers who like to write about time travel. Many writers like to puzzle through paradoxes and loops that pinch themselves off once someone has done something that would have changed history enough that their very trip through time has been cancelled out of the timeline.

Other writers like to employ the concept of the fan-shaped destiny, with multiple possibilities radiating from pivotal moments in history. I think most people would agree that the assassination of JFK is one of those pivotal moments. When I was a kid, I believed that if only he hadn't died, all of the fine dreams he had for our country would have come true. It wasn't until the presidential election of 2000 that I started to question some of my assumptions. I heard a respected reporter say that Al Gore shouldn't waste too much time grumbling about the way the electoral process had been mangled, because he was certain to win the 2004 election.

None of the other talking heads on the program questioned that assumption, but I did. No election is ever a sure thing for any candidate. And that's when I began to wonder if Kennedy could have gotten re-elected. Without the god-like shine of an assassinated president, would there be any reason to love him with such passionate devotion (unless you were a total dweeb)? If Lincoln hadn't been assassinated, would we have built his splendid memorial and chiseled all of those inspiring words into marble? Both presidents were thoroughly despised by a lot of people. The haters pretty much had to shut up after the assassinations, unless they wanted the ire of a grieving country to turn on them (not to mention the suspicions). So you could definitely get the wrong idea about what would have happened if Lincoln and JFK had been able to continue their careers.

And the assumptions don't end there. At any given time, people tend to believe that the past was a rosy place, where life was simpler, people were more virtuous, music was superior to the popular crap people listen to “these days,” and food tasted better. Somehow, they don't remember the bad stuff.

Yet at the same time, people also assume modern people are smarter. They think we're better educated, less inclined to believe superstition, stronger, and way more hip. In fact, we're so damned hip, that if we went back in time and played some modern music for those people of the past, they would think it was the greatest thing since the invention of the wheel. In movie after movie, just such a scene plays itself out, with people of the past bopping to that wonderful, superior new stuff. Never mind that every ten years or so, the old generations lament the fact that the music of the new generation sucks, big time. Plus they dress funny and they have no manners.

Music aside, simple survival in a strange place would be the biggest challenge facing any time traveler. You would have to have workable skills, and they would not include computer programming. If you were actually able to travel back in time to show those ancient people how much smarter you are, you would probably get your head handed to you on a platter (maybe literally). If you were lucky, people would feel sorry for your stupidity – a big problem, if you're trying to keep a low profile. Sticking out like a sore thumb wouldn't just make it harder to do whatever it is you went back to do, it might even do more damage. You don't want things to come to a screeching halt while everyone stops to gape at this bozo who just showed up out of nowhere and didn't know anything. The Butterfly Effect that Ray Bradbury wrote about in “A Sound Of Thunder” (also mentioned by Jake in 11/22/63) could only get worse under those circumstances.

According to Bradbury, the Butterfly Effect would be magnified exponentially, depending on how far back you went. Yet, common sense would not necessarily stop a time traveler. You'd be asking yourself, Just how much will actually change? If I can do a greater good, will any harm that occurs as a result of people not meeting people, intersections failing to happen, new patterns emerging, be worth it? Maybe you would hope that things would be different-but-better. Or at least still okay. Or maybe you would selfishly pursue your own agenda and not give a damn.

Jake isn't selfish, though he does get wrapped up in the past. He at least has an excuse – his mission is a noble one, once he commits himself, and in the meantime, maybe he can do some good in the more ordinary lives he intersects. You don't blame him when he realizes that he's happier in the early 1960s than he was in the 21st century. But he's screwing with time, and you have to wonder how big the bill is going to be when it finally comes due. And the mission itself seems impossible – how can he stop such a gigantic event? Maybe he can't. Maybe he should just disappear into the 60s and lead his new (increasingly un-fake) life. It might not lead to a happy ending, but it might be as happy as any life can be.

But once he's seen Lee Harvey Oswald, that's no longer possible. The smaller questions generate bigger ones, until it finally all boils down to one really big question: Can Jake sacrifice personal happiness in order to save the world?

That's what you'll find out when you read 11/22/63. But I've got a question of my own. Everyone wonders how things might have turned out if things had happened differently. What if Oswald had failed to shoot Kennedy? What if the assassination attempt against Hitler had succeeded? What if someone had realized that Harris and Klebold were bat$#*t crazy in time to stop them? Would the world be a better place, or just a different one?

I'd like to go one further than that. What if time is already doing the best it can? What if, once you average it all together, everything that has happened really is the best that can happen? Some people might be discouraged or even horrified by that idea. But if you have to take the bad with the good, maybe you have to take the good with the bad, too. Maybe you have to admit that many wonderful things have happened, all of us have had at least some happiness in our lives. Medicine is better, science is exploring new frontiers, and we have centuries of art, music, and literature at our fingertips. On average, we have more time to spend with our loved ones than people have ever had, in the history of the human race.

We can instantly download good books like 11/22/63. Maybe that's the best argument of all.

One more thing – I listened to 11/22/63 as an audiobook. The reader, Craig Wasson, was wonderful. He deserves an award for his performance. I'll be looking for more of his work.

Monday, December 19, 2011

Suffering For Your Art

I think writers are luckier than artists and composers. Most of us don't start out with the ambition of creating great art. Usually, we just want to tell an entertaining story and get people to buy our books. We want them to do that so we can keep writing. The way it usually turns out, people mostly don't buy our books, a fact that causes us both financial and emotional distress. But we keep writing anyway. By the time we figure out we're not going to be able to make a living with writing, we're already addicted to the process, and it's too late. We hold onto our day jobs and hope that some day the urge to write will go away and that we'll find a cheaper hobby. But we do have much in common with artists and composers. We all suffer. And that suffering isn't just due to lack of money and acclaim.

This situation is beautifully illustrated by the movie, Untitled. We see two brothers struggling to be the best they can be. One is an artist who has managed to make money at what he does, yet he can't seem to get critics and gallery owners to notice him or show any respect for his work. The other is a gifted musician who is also a composer – but the music he creates is far from commercial. Audiences walk out on him when he performs this music. He tells his brother, The Artist, that he's going to give it three more years – and if he doesn't “make it” by then, he's going to kill himself.

This is a line that makes you laugh – not because you think it would be funny if this guy killed himself, but because you actually understand how he feels. He's out there, a voice in the wilderness, and he really believes in what he's doing. His brother does too. Both of them have something all creative people share: hubris. It's a trait that flies in the face of American values, an overconfidence mingled with a lack of modesty. Yet we can't work up the nerve to create stuff without it. We draw, and paint, and compose, and write, and we show what we've done to the world. When the world ignores us – or worse, laughs at us – it's really painful.

Besides their suffering, the two brothers in Untitled share something else – or rather, someone. They both get involved with a young woman who's a gallery owner. She is strongly attracted to artists who are as unpleasant, unappealing, and weird as possible, because she believes they are true pioneers. Her great talent is to peddle this idea to wealthy patrons, and she actually makes her case very well. Despite her preference for unappealing art, she reps the artist brother, selling his “pretty” paintings to banks and hotels, making a lot of money for him and for herself. This allows her to mentor the weird artists she truly loves. But when the artist brother wants to have his own show, she puts him off. She thinks he's not good enough, but she can't quite come out and say that to him. We look at his paintings, and we can see her point of view. They're pretty, but seem kind of boring.

The gallery owner also thinks the composer brother isn't good enough. Yet she can't resist his weirdness, or the dissonance of his music, so she promotes him. She lets him perform at her gallery, and the audience loves him. But along with the applause and the appreciation, there's also laughter – they think he's being deliberately funny, and he's not. This really humiliates him – but the performance makes it possible for the gallery owner to get him a commission. For the first time in his life, he's got to come up with a serious composition that someone else is paying for.

For a writer, this is comparable to selling your first novel. You believe you've finally got your foot in the door. Finally getting noticed is heady stuff, you're ready to take the world by storm. But bookselling is a commercial business, and what happens to new books is that they get released as if they were hamburgers. You've got maybe a month or two to sell as many hard copies as you can in a Brick & Mortar store, and then you're pretty much off the radar. These days, with ebooks and internet, you've got some options writers didn't have before – you can petition bloggers to review your book, try to get guest blogs, try to make some happy noise on your social media networks. Basically you become the best carny barker you can be, regardless of what your publisher is willing to do to promote your book (which is generally almost nothing).

But even if your initial sales are enough to win you another book contract, you discover another painful truth. Your publisher has pigeonholed you as a certain type of writer, and they are only willing to consider certain story ideas. In a way, you've got to keep writing the same book, over and over. If you try something that's too different from what they expect of you, they won't buy it.

For the artist brother in Untitled, this is actually not a problem. His paintings are all very much alike – that's just what he wants to paint. But in his own way, he has still been pigeonholed by the gallery owner. She believes a show of his work will flop. And at this point in the movie, you agree with her. When the paintings are seen individually, they look pleasant, but uninspired.

Meanwhile, the composer brother seems to be blossoming. He has to direct other musicians, and for the first time, there are rumors of actual moolah materializing. He gets to work with a singer who hates his guts. She's talented, and very opinionated, and harbors suspicions that he's trying to sabotage her by making her look ridiculous. Yet she stays on board, and he learns more about directing. Every time they perform you still want to laugh, but you begin to realize that part of the reason you're laughing is that the music is not just “weird,” it's witty. There really is an inherent beauty to unstructured sound – you hear it every time you stop to listen to distant thunder, or wind chimes, or the sound of water bubbling over rocks. At this point the film has performed a subtle shift – the characters are seeing and hearing things differently, and so are you. You begin to realize that the gatekeeper in the movie, the gallery owner, is not just helping the artist and the musician. She's hurting them, too.

This is what gatekeepers always do, whether they're gallery owners, critics, recording executives, or publishers. They can turn you into a professional. They can make it possible for you to achieve critical and/or financial success. But in doing so, they become the bosses of your career. They decide what you're going to write, paint, and compose – and what you're not going to write, paint or compose. They decide what ideas and projects are worth pursuing. It's very hard to succeed without them. But once you've teamed up with them, your choices become very limited. And worse, those gatekeepers who let you in will eventually shut you out for good. Up until recently, once they closed the door on you, you were done.

Now things are shifting around pretty drastically in the publishing world. They're shifting in the music world too, though It's still hard to say what's happening with art. I suspect we still have some gatekeepers – like Amazon, Barnes & Noble, YouTube, Google – But so many people are using these services, they don't seem to have the time or the inclination to micro-manage anyone's career (yet). For the time being, we writers and artists and composers have the option of plying our trade online without getting the approval of a gatekeeper. Many of us are finding out how hard, exciting, satisfying, and aggravating that can be. Probably the best thing about it is that we get to decide what we've got that's worthy to show the world. Many people would argue that's also the worst thing about it. The possibility of looking ridiculous is scary – you could lose credibility, rack up hundreds of bad reviews, look like a fool to the world.

But sooner or later, you have to risk that possibility. Because you're creative, and this is how you can succeed, even when the gatekeepers won't let you in – or when they've decided you're done, and shut you out for good, which is what happens to most writers, and artists, and composers. You can take the guff and slink away with your tail between your legs, or you can seize the day.

And that's exactly what the brothers do, in Untitled. Just when you think they're going to keep knuckling under to the gallery owner, they decide they have to do what they have to do. The composer writes a composition all right, but when the time comes to perform it for the wealthy patron who bankrolled it, the composer emulates the gallery owner's favorite artist, a guy who makes “invisible” art. The composer makes soundless music.

And the patron demands his money back. But that's okay, the composer is ready to stride off in his own direction, he really knows what he wants to do now. He doesn't need to follow anyone else's ideas about what music he should make. His brother, the artist, also asserts himself – he demands his own show. He gets it, simply because all of the other avante-garde artists have abandoned the gallery owner by this time (apparently they're a fickle lot). So she fills her gallery with the “pretty” art. And another odd thing happens. Once you see all of those paintings together, they look beautiful and inspiring. You realize that the reason the paintings look pleasant-but-sort-of-boring by themselves, is that they were all really part of a larger work, something that's still in progress.

So the gallery owner was both right about him and wrong about him. She was helping him along and holding him back. Gatekeepers do filter a lot of amateurish stuff out before the wider public can ever see it. Sometimes they also mentor talented amateurs until they turn into professionals. Once you've got a gatekeeper in your corner, you really want to please them, you're inclined to see things their way. It's actually a little sad how badly you want to please them. If you become uber-successful, as a handful of people do, this relationship may shift until you're the one who needs to be pleased. I think we all hope for that outcome. More often, you just get strung along until you're finally dropped.

But in a way, that's the luckiest thing that could happen to you. You don't have to work up the courage to take the plunge, sever your ties with a gatekeeper, and possibly assassinate your career – because you've got no other choice. So what you do instead is make the best of it. You try to figure out what your options are. It's hard work, but not really any harder than becoming an artist, or composer, or writer in the first place. You suffer when people laugh at you, or ignore you, or write lengthy opinions about why you suck. You don't get much money, or much critical acclaim, but you still feel driven to express yourself. Every time you put something out there, you're taking a big risk, and it's scary.

The compulsion to create overcomes all that. And, after all, it's not slings and arrows every second. They say that anyone who can be discouraged from [fill in the artistic endeavor], should be discouraged. And that's the most essential thing all artists/writers/composers have in common. We can't be discouraged. We dream. We dream big.

Those qualities, above all else, may be what really define us.